The Olympic Village, once a simple solution for housing thousands of athletes, has transformed over the past century. What started as a basic logistical necessity is now a powerful tool for urban planning, capable of creating entire new neighborhoods and leaving a lasting legacy long after the Games conclude.

As cities prepare for events like the upcoming Milano–Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics, the design of these villages reveals shifting priorities—from temporary structures to permanent, sustainable communities designed with the future in mind.

Key Takeaways

- Olympic Villages began as purely functional, temporary accommodations focused on logistics and security.

- By the mid-20th century, they evolved into experiments for large-scale housing projects, often repurposed after the Games.

- Modern Olympic Villages are now integral to long-term urban regeneration strategies, creating new districts with lasting infrastructure.

- Contemporary designs prioritize sustainability, flexibility, and adaptability, with post-Games use planned from the initial stages.

- The Milano-Cortina 2026 Games are pioneering a decentralized model, using multiple sites to minimize environmental impact.

The Early Days A Logistical Necessity

In the first few decades of the modern Olympics, housing athletes was a practical problem, not an architectural statement. The primary goal was to provide simple, secure lodging close to the competition venues. These early efforts were more about operational efficiency than creating a community or a lasting urban feature.

An initial attempt was made during the 1924 Paris Summer Olympics, where temporary wooden cabins were constructed near the stadium. While functional, this arrangement was little more than organized lodging. The focus was on proximity and control, ensuring athletes could be managed easily within a contained environment.

These early compounds were defined by standardized housing, straightforward layouts, and minimal public space. They were designed to serve a single purpose for a very short period, with little thought given to their existence after the closing ceremony.

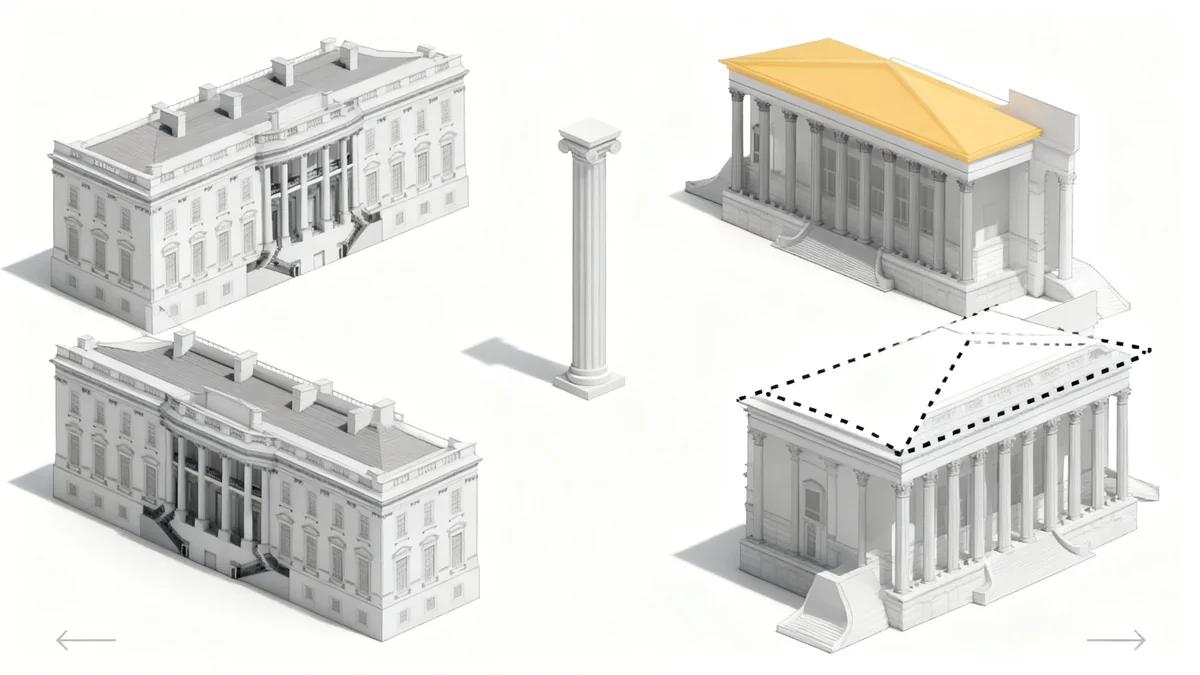

What Defines an Olympic Village?

An Olympic Village is a residential complex built for the Olympic Games, typically within an Olympic Park or elsewhere in the host city. It houses all participating athletes, as well as officials and athletic trainers. The concept is to create a self-contained community to meet the unique needs of thousands of competitors during the event.

A New Vision Villages as Housing Prototypes

The post-war era brought a significant shift in thinking. Amidst housing shortages and a rise in state-led urban planning, organizers began to see the Olympic Village as more than just temporary shelter. It became a unique opportunity to experiment with new models of collective living that could benefit the city long-term.

The 1960 Rome Summer Olympics marked a turning point. The village was conceived from the very beginning as a permanent residential district. Instead of an isolated compound, planners designed a neighborhood complete with apartments, services, and infrastructure intended for public use after the Games.

This was a fundamental change in philosophy. The village was no longer just a temporary system but a prototype for modern housing, testing how large-scale collective living could be organized.

This trend continued with the 1968 Grenoble Winter Olympics. The housing blocks built for athletes were designed for easy conversion into social and mixed-use housing, seamlessly integrating into the city's fabric. These projects served as controlled experiments, limited in scope but influential in shaping future urban housing policies.

However, even these innovative projects remained largely self-contained. While they addressed how people could live together within the village, their connection to the surrounding city was often a secondary consideration.

Urban Catalysts Reshaping Modern Cities

As the Olympic Games grew in scale and complexity, so did the ambition for the villages. Planners began to envision them not just as housing projects but as powerful catalysts for reshaping entire sections of a city. The village became a key instrument for accelerating large-scale urban change.

The London 2012 Olympic Village is a prime example of this strategic approach. Built on a formerly industrial site in East London, the project was designed to be the foundation of a new urban district. After the Games, the athlete housing was converted into thousands of new homes, and the entire area was transformed into the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

London 2012 by the Numbers

- The Olympic Village provided housing for over 17,000 athletes and officials.

- Post-Games, it was converted into approximately 2,800 new homes, including affordable housing.

- The project anchored the regeneration of 560 acres of land in East London, creating a new park, schools, and health centers.

This model treated the village as an active piece of city-making. New streets, public spaces, and transportation links were designed to connect with existing urban patterns, ensuring a smooth transition from an event-specific environment to an everyday neighborhood. Housing remained a central component, but it was framed within a much broader ambition to reorganize the city's structure and public life.

Designing for the Future Adaptability and Sustainability

More recently, the long-term legacy of the Olympic Village has become a primary concern from the earliest planning stages. Instead of treating the post-Games conversion as an afterthought, contemporary projects are designed for change from day one.

The Tokyo 2020 Olympic Village showcased this modern approach. The project incorporated strategies of reuse, temporary construction, and phased development. For example, the Village Plaza, which served as the main social hub, was built using 40,000 pieces of timber donated from 63 Japanese municipalities. After the Games, the structure was dismantled, and the timber was returned to be reused in local projects.

This emphasis is on flexibility. Housing layouts, building systems, and public spaces are all planned to be easily adapted for everyday urban life once the event concludes. Time itself has become a key design parameter, with the village seen as part of a long, evolving process rather than a fixed outcome tied to the Games.

The Milano-Cortina Model A Decentralized Approach

Looking ahead, the Milano–Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics is breaking from the traditional model of a single, centralized village. Instead, it will feature multiple housing sites spread across Milan and the Alpine regions, tailored to the unique geography and needs of each location.

This decentralized strategy reflects a new way of thinking about the relationship between the Games and the host territory. The approach combines new construction with the adaptation of existing buildings and temporary solutions.

- In Milan: The main village is being built on a former railway yard, part of a larger urban redevelopment project. It is designed from the outset for post-Games conversion into student housing and affordable homes.

- In Cortina and other mountain locations: The focus is on temporary villages designed for minimal environmental impact and complete reversibility, preserving the sensitive Alpine landscape.

This flexible framework allows the Olympic housing to support the event without imposing a massive, permanent structure on every location. It reinforces the idea that the Games can adapt to the city, rather than forcing the city to adapt to the Games.

From simple cabins to complex urban districts, the evolution of the Olympic Village mirrors our changing understanding of how cities are built and what legacy a global event should leave behind. It serves as a recurring, high-stakes experiment in building for both the immediate moment and the distant future.