A major exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is reframing the history of 20th-century photography, showcasing how studio portraits from West and Central Africa became powerful tools for self-expression and political identity. Titled "Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination," the show argues that these images were not just personal keepsakes but active participants in shaping a new, confident vision of Blackness on a global scale.

Running until July 2026, the exhibition gathers iconic works from the 1950s and 60s, a period of immense change as numerous African nations gained independence. It connects these historical photographs with contemporary art, tracing a lineage of visual language that crossed the Atlantic and influenced cultural movements in both Africa and the United States.

Key Takeaways

- MoMA's "Ideas of Africa" exhibition explores the role of studio photography in post-independence Africa.

- The show features legendary photographers like Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, and James Barnor.

- It highlights a transatlantic dialogue between African photographers and the "Black is Beautiful" movement in the U.S.

- The exhibition views these portraits as acts of self-definition and political imagination, not just documentary records.

Defining an Era of Optimism

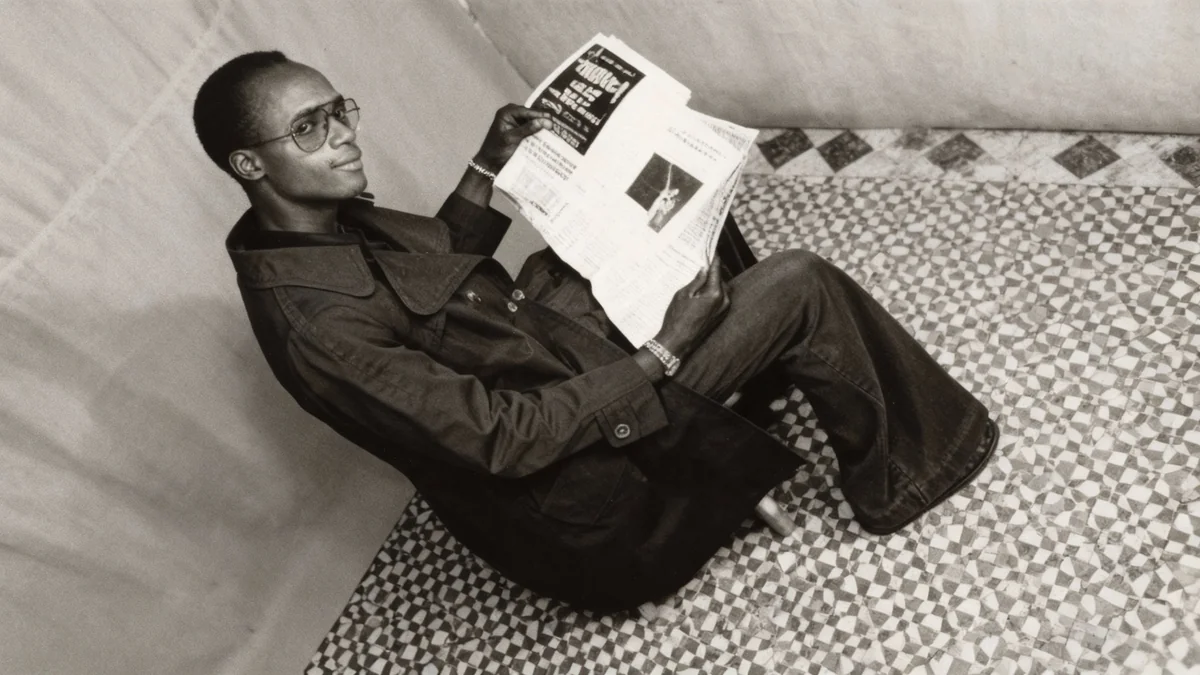

In the mid-20th century, photography studios in cities like Bamako, Accra, and Kinshasa became vibrant spaces of creation. As nations moved toward independence, citizens stepped in front of the camera to project a vision of their future. These were not candid snapshots; they were carefully constructed performances of identity.

Men in sharp suits and women in patterned dresses posed with confidence, their gazes direct and self-assured. Photographers like Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé in Mali became masters of this new form of portraiture. They provided backdrops, props, and an environment where their clients could present their ideal selves to the world.

The exhibition emphasizes that these sessions were collaborative acts. The sitters were not passive subjects but active authors of their own image, using clothing, posture, and accessories to articulate a modern African identity, free from colonial representation.

The Inspiration Behind the Exhibition

The conceptual framework for the show draws from Congolese author V.Y. Mudimbe's 1994 book, "The Idea of Africa." Mudimbe's work critically examined how Western perspectives constructed and often distorted the concept of "Africa." This exhibition seeks to counter that by presenting a narrative where Africans themselves define their own image and meaning through the lens of a camera.

A Transatlantic Visual Conversation

One of the exhibition's central arguments is that the influence of these photographs extended far beyond their local communities. They became part of a larger, transatlantic conversation about Black identity and pride. The show traces a direct line from the studios of Accra to the streets of New York.

The work of Ghanaian photographer James Barnor, who worked in both Accra and London, is presented alongside that of Kwame Brathwaite, a key photographer of the "Black is Beautiful" movement in New York during the 1960s. This pairing illustrates a powerful call-and-response across the ocean.

"In focusing on imagination, I’m encouraging people to be attuned to the interpretive potential of a photographic portrait, not solely its documentary utility," says MoMA curator Oluremi C. Onabanjo. She explains that the inclusion of artists like Brathwaite and Barnor "speaks to the literal transmission of Pan-African ideas and images across space and time."

The confident styles and proud self-representation seen in the African portraits resonated with and helped fuel the aesthetic of Black pride movements in the United States. The images circulated through a growing network of magazines and publications, creating a shared visual language for Black people globally.

A Pivotal Year in History

The historical context of these photographs is crucial. The year 1960 alone saw 17 African nations gain their independence, ushering in an era of unprecedented optimism and cultural flourishing that is palpable in the portraits from this time.

The Photographers and Their Studios

The exhibition brings together a remarkable collection of artists who defined the genre. Their work, seen together, reveals a shared commitment to capturing the spirit of their time.

Key Artists Featured:

- Seydou Keïta (Mali): Known for his masterful use of pattern and composition, Keïta's portraits are celebrated for their elegance and dignity.

- Malick Sidibé (Mali): Famous for capturing the vibrant youth culture and nightlife of Bamako, Sidibé's work is filled with energy and joy.

- James Barnor (Ghana): His work bridges continents, documenting life in both newly independent Ghana and the growing African diaspora in London.

- Sanlé Sory (Burkina Faso): Sory’s studio portraits often feature playful and imaginative backdrops, reflecting the aspirations of his clients. His piece, L’Intellectuel, is a notable work in the collection.

- Jean Depara (Democratic Republic of Congo): Depara captured the lively social scene of Kinshasa, offering a glimpse into the city's post-independence nightlife.

These photographers were not just technicians; they were cultural figures who helped their communities visualize a new world. Their studios were more than just businesses; they were stages for imagining freedom.

Continuing the Dialogue

"Ideas of Africa" is not purely a historical survey. It deliberately includes contemporary artists to show how these foundational ideas continue to evolve. Works by artists such as Samuel Fosso, Silvia Rosi, and the collective Air Afrique are placed in conversation with the mid-century masters.

These contemporary artists often use self-portraiture and historical references to explore complex themes of identity, memory, and diaspora. Their inclusion demonstrates that the project of defining and redefining African identity through the photographic image is an ongoing process.

A reading room within the exhibition further illustrates how print culture helped disseminate these powerful images, moving them from private albums into the public sphere and cementing their role in shaping a collective political imagination. By avoiding nostalgia, the exhibition presents these photographs as dynamic evidence of how independence was not just achieved, but also profoundly imagined.