New research from the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, D.C., suggests that Johannes Vermeer's painting, Girl with a Red Hat (circa 1664–67), may conceal an earlier portrait of a man beneath its surface. This finding could reshape understanding of Vermeer's artistic process and early career, potentially adding a unique male portrait to his known body of work.

Key Takeaways

- Advanced imaging revealed a male portrait under Vermeer's Girl with a Red Hat.

- The underpainting's style, initially thought to be by another artist, is now considered consistent with Vermeer's early, looser brushstrokes.

- If confirmed, this would be Vermeer's only known male portrait and among his earliest works.

- The hidden figure's clothing dates to 1650-55, suggesting an earlier period for the work.

- The discovery opens new questions about unidentified works by Vermeer and his contemporaries.

Underpainting Reveals Hidden Figure

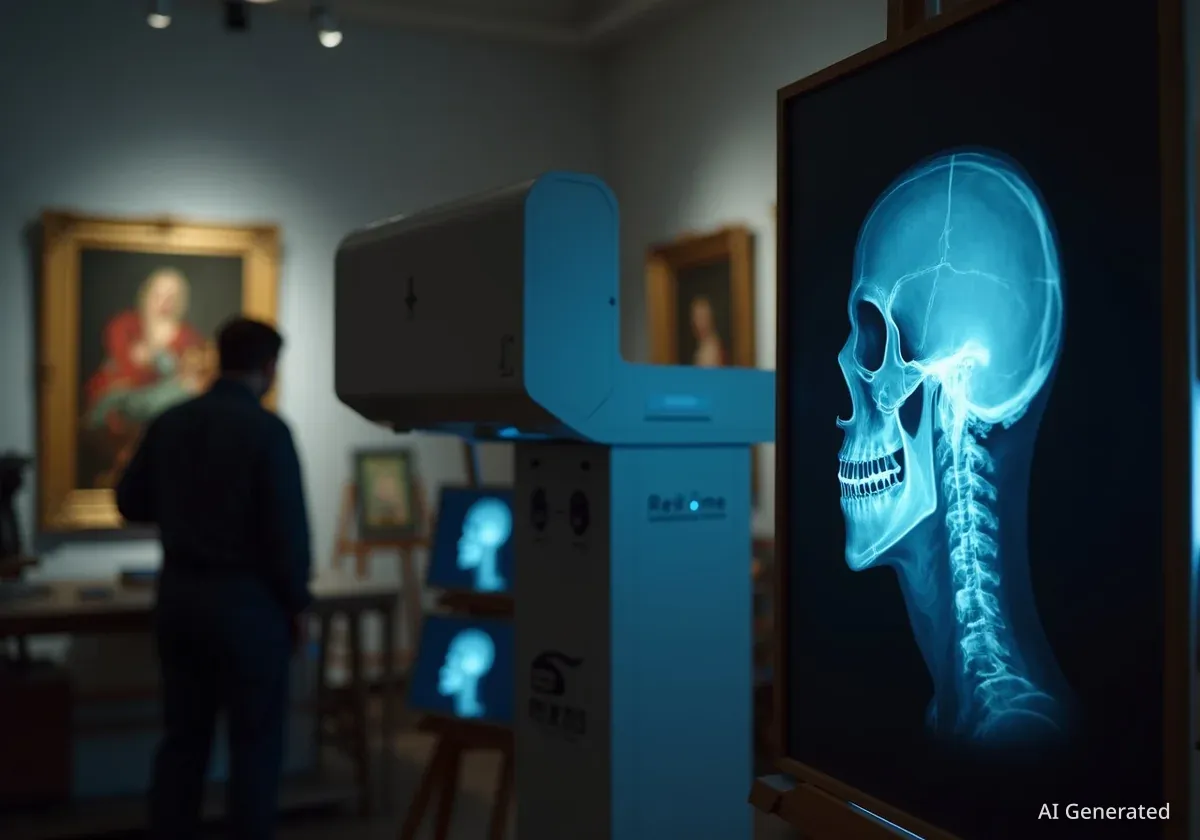

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Gallery of Art initiated a detailed examination of four paintings attributed to Johannes Vermeer. Specialists used advanced imaging techniques to look beyond the visible layers of paint. This process allowed them to virtually penetrate the surface and analyze the artist's underlying work.

Microscopic examinations of the paintings' surfaces provided further insights into Vermeer's creative methods. These studies focused on how paint was applied and layered. The combined techniques revealed an unexpected image beneath Girl with a Red Hat: a portrait of a man.

Interesting Fact

The NGA's conservation studio employed a combination of X-ray fluorescence spectrometry and infrared reflectography to peer through the paint layers. These methods allow art historians to see preparatory sketches and earlier paint applications without damaging the artwork.

Revisiting Artistic Attribution

Initial analysis of the underpainting indicated a loose brushwork style. This led some experts to believe an unidentified artist, not Vermeer, had created the male portrait. The style appeared uncharacteristic for Vermeer's refined finished works.

However, further studies challenged this early conclusion. Art schools today often teach that artists begin with looser underpaintings. These initial layers are completed quickly before the master refines the work. This process is considered typical for many artists, including Vermeer.

"Vermeer’s underpaintings were consistently looser and completed more quickly, before the master went back in to refine the work," explained one art historian involved in the research. "This is a common practice, even today."

This revised understanding suggests the underpainting's style is consistent with Vermeer's own preparatory stages. The argument now being made by NGA specialists is that the male portrait could indeed be by Vermeer himself.

Dating the Hidden Portrait

The man in the underpainting wears a wide-brimmed hat and a collar with a tassel tie. Art historians have dated this specific costume to the period between 1650 and 1655. This timeframe is significant because it would place the painting among Vermeer's earliest known works.

Currently, Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (1654-55) holds the distinction of being Vermeer's earliest recognized painting. If the hidden portrait is confirmed as Vermeer's, Girl with a Red Hat could be an even earlier example of his work, providing new context for his initial artistic development.

Background on Vermeer's Early Career

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) was a Dutch Baroque Period painter known for his domestic interior scenes of middle-class life. Very little is known about his early training and artistic influences. Discovering an early work could shed light on his formative years as an artist.

A Unique Male Subject

A confirmed male portrait by Vermeer would be a significant discovery for another reason. It would be his only known male portrait. While paintings like The Astronomer (1668) and The Geographer (1668) depict men, they are generally considered genre scenes or allegories rather than direct portraits.

This potential portrait offers a rare glimpse into Vermeer's handling of male subjects. It could deepen understanding of his range and preferences, especially during his formative years. The research therefore provides a greater context to the artist’s process and early career, which remains largely mysterious.

Vermeer's Known Works

Only about 35-36 paintings are widely attributed to Johannes Vermeer. Each new discovery or re-attribution significantly impacts the study of his life and art. The scarcity of his works makes any new finding highly important.

Ongoing Debate and Future Possibilities

Despite the strong arguments, the theory that the male portrait belongs to Vermeer "has not yet been proven or denied," as reported by The Art Newspaper. The research is ongoing, and experts continue to analyze the evidence.

This investigation also opens the door to other possibilities. An inventory compiled after Vermeer’s death in 1676 indicates he owned two male portraits by his fellow Delft artist, Carel Fabritius. This raises the question: could the hidden work have been painted by Fabritius, with Vermeer later painting over it?

Carel Fabritius was a talented artist and a pupil of Rembrandt. He died young in the Delft gunpowder magazine explosion of 1654. Only about a dozen works by Fabritius are known to exist. If the hidden portrait was indeed painted by him, it would be an impactful finding for his limited body of work as well. This ongoing research promises to offer further insights into the Dutch Golden Age of painting, regardless of the final attribution.

- Further analysis: Scientists continue to examine the painting for more clues.

- Historical context: The discovery provides a chance to learn more about art practices in 17th-century Delft.

- Artist connections: It could reveal previously unknown links between Vermeer and Fabritius.