Many art schools promise a gateway to a successful artistic career, but the reality for many graduates often involves significant debt and uncertain job prospects. This growing issue highlights a mismatch between the high cost of a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degree and the practical skills artists need to thrive in a competitive marketplace.

Key Takeaways

- Art school tuition has steadily increased, shifting the financial burden to students.

- Many MFA programs focus on theory, often neglecting essential business and survival skills for artists.

- The pursuit of institutional prestige fuels the cycle of rising costs and debt.

- Alternative art education models offer different paths without the high financial commitment.

The Rising Cost of Art Education

The Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degree emerged as the terminal degree for artists in the mid-20th century. Institutions like Yale and CalArts helped establish the MFA as a mark of prestige and a credential for academic employment. This shift integrated studio practice into the university system, creating a professional category of "artists."

However, the financial landscape of higher education changed dramatically during this period. The Higher Education Act of 1965 expanded federal aid, but increasingly favored loans over grants. This fundamental shift meant students bore more of the cost.

Historical Context of Higher Education Funding

In the 1970s and 1980s, this trend solidified. Political leaders, including Ronald Reagan, advocated for higher education as a private investment rather than a public good. This led to cuts in federal aid and a conversion of grants into loans, reframing education as an individual responsibility. Historian Christopher Newfield identifies this era as the beginning of tuition's steep ascent.

The result for art education was clear: more MFA programs, more students, and significantly more debt. Prestige became the primary product, and student loans became the mechanism. Students, especially those without substantial family wealth, often found themselves burdened with considerable financial obligations.

The Promise Versus Reality

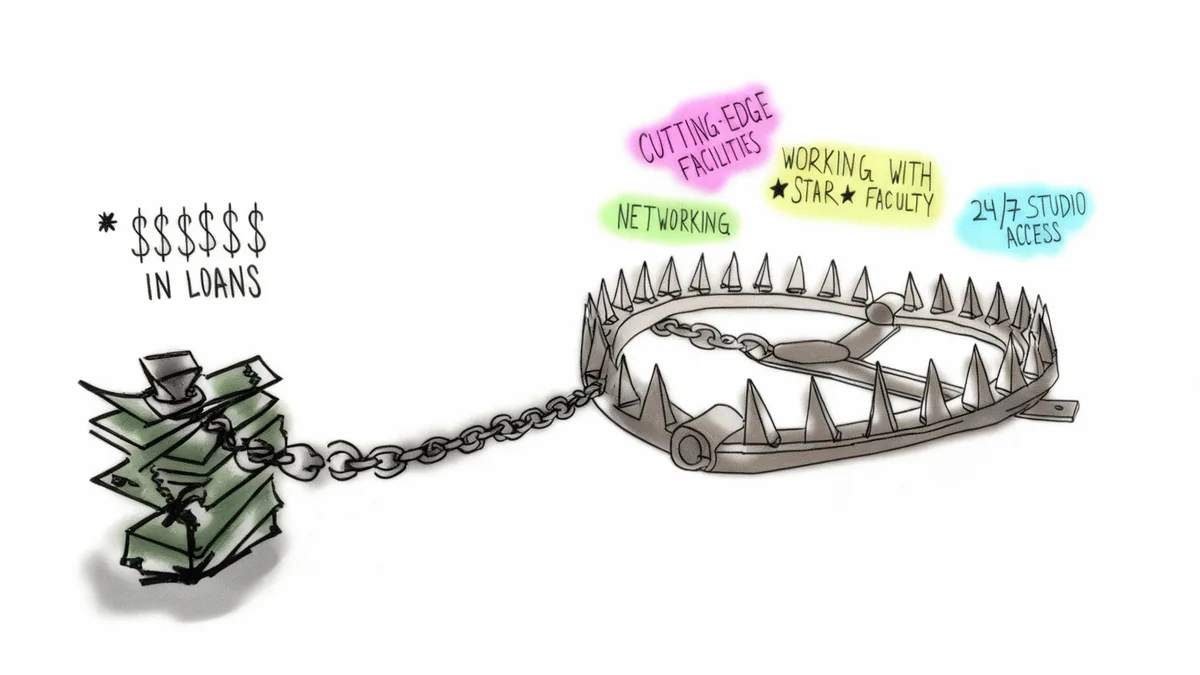

Art schools frequently market themselves by highlighting star faculty and state-of-the-art facilities like print shops, foundries, and digital labs. The implicit message is that proximity to these resources and renowned figures will lead to career success, including gallery shows, residencies, and teaching positions.

While some graduates do achieve these outcomes, many others finish their programs with substantial loans, limited job security, and skills that do not fully align with the demands of the art market. The system often appears designed to sustain institutional prestige rather than ensure practical success for every student.

“The escalating cost of higher education has always been a way to keep people out. Rising tuition doesn’t just reflect inflation. It replicates a system that treats access to radical thought as something that can only be bought with money.”

This cycle creates a feedback loop: a few graduates gain visibility, the school claims credit, and new students enroll, hoping to follow a similar path. What was once a system for a small elite has expanded without adapting to the evolving realities of the art world.

Gaps in Practical Training

Despite the high tuition fees, many art school programs exhibit significant gaps in practical training. Students often graduate without understanding basic professional skills vital for an artistic career. These include creating a curriculum vitae (CV), negotiating gallery splits (typically 50/50), understanding standard artist fees, negotiating contracts, or filing taxes as freelance artists.

Essential Missing Skills

- Grant writing

- Archiving and documenting artwork

- Shipping and logistics for art

- Self-advocacy and professional communication

- Understanding art market economics

Instead, many programs prioritize art theory and critique. While these are valuable for intellectual development, they often fall short in preparing artists for the financial and logistical challenges of sustaining a creative practice. The focus on theory can leave graduates unprepared for the business side of being an artist.

Teachers acknowledge that they cannot teach someone "how to be an artist." A more honest approach might involve equipping students with tools to honor their creativity while also providing the practical skills needed for survival. The financial burden disproportionately affects Black, Brown, and first-generation students, who may also struggle to find mentors who understand their unique backgrounds and challenges.

The Role of Debt as a Gatekeeper

Debt effectively acts as a gatekeeper in the art world. Students who can afford unpaid internships, residencies, or international study programs gain a significant advantage. Those without such financial flexibility are left to scramble, often facing greater obstacles.

Many institutions promote diversity initiatives, but without substantial financial support, these efforts can appear largely performative. Cultural scholar Sara Ahmed notes that diversity often serves as institutional branding, signaling progress without genuinely addressing underlying inequities. This can lead to a situation where schools extract cultural capital from diverse students while failing to provide adequate support, leaving them with disproportionate debt and fewer opportunities.

The art world benefits from an oversupply of aspiring artists. This abundance fuels competition, undermines solidarity among artists, and can make artists feel disposable. The message is often that there will always be more individuals willing to endure debt and scarcity for a chance at recognition.

Exploring Alternative Models

While art school offers unique benefits like community, dedicated time, and space for experimentation, the question remains whether these are worth the escalating price tag and potential debt. Many argue that the current system ties artistic development to a cycle of exclusion.

Fortunately, alternative models for art education exist. Black Mountain College, active from the 1930s to the 1950s, offered an interdisciplinary approach where painters, poets, dancers, and musicians collaborated. The lines between faculty and students blurred, fostering an environment that produced influential figures like Josef and Anni Albers, Merce Cunningham, and Ruth Asawa. This model demonstrated that rigorous art education could thrive outside traditional accreditation.

More recently, events like the Alternative Art School Fair in Brooklyn have showcased various non-accredited programs, including residencies, critique groups, and collectives. The Black School, founded by Shani Peters and Joseph Cuillier III, exemplifies this, linking art with Black politics, education, and community building, while exploring sustainable funding models.

These examples highlight that there are many ways to learn, build networks, and sustain an artistic practice without incurring massive debt. The challenge lies in recognizing and valuing these diverse educational paths as seriously as traditional MFA programs.

Moving Forward

The art school debt trap persists because it benefits institutions through tuition and cultural capital, and the broader art world through a steady supply of aspiring artists. Students from less-resourced backgrounds often navigate systems not designed to support them.

Breaking this cycle requires a refusal to see art school as the only path to legitimacy. It means demanding greater transparency regarding graduate outcomes, integrating essential survival skills alongside theoretical critique, and valuing non-accredited, collective models. Understanding how policy shifts, such as those that privatized education, continue to shape access to art study is also crucial.

Art schools alone cannot solve these systemic issues. The opportunity now lies with artists themselves to build parallel systems of support, grounded in honesty, solidarity, and mutual care. This approach can empower artists to define their own paths and prove their worth without succumbing to the pressures of an expensive and often unforgiving system.